Co-op as Store Becomes Co-op as Community

We can no longer (verb)_____ in isolation. Try these verbs: Learn. Vision. Plan. Invest. Be. Then try your own!

Nearly three years ago, the board of directors of the Brattleboro Food Co-op adopted new Ends Policies, statements defining our fundamental aims. A minor celebration followed this conclusion of a decade-long process of developing the board’s framework using the Policy Governance system. What was not known or celebrated at the time was the profound influence these policies would have on the long-range strategic thinking guiding the cooperative.

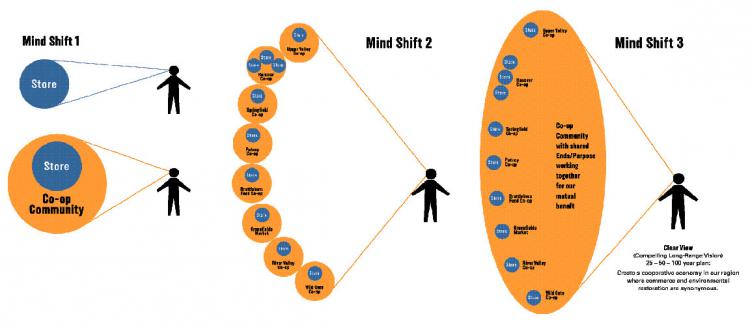

The most significant outcomes so far are the changes in how we (co-op board and management) think about things. These changes are so prevalent that we named them mind shifts. And because it is not easy to break old patterns and learn new ways, we have a motto: “No longer ________ in isolation.” (Insert these verbs in the blank and you’ll get the idea: learn, vision, plan, invest, be.) While we did not map out this series of events in advance, we did take each step with focus and intentionality—and one thing led to another, but some were completely unexpected! Here’s the story as it unfolded.

From “It’s a store” to “We are a community”

For a few months following the April 2002 meeting, we continued our celebration and our familiar patterns: meeting, monitoring, and appreciating our well-developed policy structure. But later that year it became apparent that the enormous amount of meeting time we had spent on policy development could be directed elsewhere. The question became, “How should we use our time?”

In December 2002, we had a “What’s on your Mind” meeting. We reviewed the topics of our recent annual membership meetings:

2000: BFC meets downtown revitalization

2001: BFC leads the way: No-GMOs and Sustainable = Buy Local

2002: Theory of Sustainability/Whole Systems

We took note of articles in Cooperative Grocer calling on boards to “look at the big picture.” We acknowledged the “know how” of our management team to successfully operate the store and our monitoring system’s ability to provide accountability with minimum use of time. We then committed ourselves a new use of our board time. It was time to look outward. The topic chosen for our 2003 annual meeting: “Can there be a cooperative future?”

As a symbol of change, each board member received a beautiful coffeetable book, Fatal Harvest—The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture, a collection of essays addressing one of our questions: “Where do we want our food to come from?” Andrew Kimbrell, the editor, provides this challenge to readers in his introduction: “We must see ourselves as creators rather than consumers.”

It was at this December meeting that a board member drew a picture of our first mind shift on a flipchart (see illustration: Mind Shift #1). Earlier in the year we had asked for member input on the possibility of moving our store to a location out of downtown. Member responses told us much more than we had anticipated. At several well-attended member events we heard again and again members describing our co-op without talking about food. They described the social aspects—the value of the co-op to the community, the co-op as community.

From “Green building design” to “Create a regenerative marketplace”

We acquired the downtown site of our existing store in January 2004, and in March co-op management began working with a consultant who specialized in whole/sustainable systems and green building design. The assumption was that since we owned the building, someday we would likely build or renovate, and that process should be guided by our new Ends Policy: creating sustainable community.

What emerged from an admittedly messy three-month process (are we talking about a building or sustainable community?) was the next level of learning about our Ends Policies and how a store fits within the scope of community. Here’s an excerpt from the report summarizing some of our discussions:

The co-op has an Ends Policy that deeply embraces environmental responsibility and health—both social and natural system health.

Any activity the co-op engages in, including the planning of a new building, needs to be based on the Ends Policy—the ultimate basis from which to evaluate if an activity or assignment has been successful.

In designing a sustainable project it is necessary to evaluate and prioritize where the opportunities are to save energy, improve water quality, reduce the toxins entering the environment, reduce resource use, and so on.

With a food store it is likely that global and transcontinental food transport alone burn more fossil fuel than that which can be saved by an energy efficient grocery store. An additional burden is that commercial agriculture processes are intensely fossil fuel dependent both for energy and fertilizer.

Besides the obvious need to make the store energy efficient and environmentally responsible in its design, it was apparent that greening the store’s products and purpose for being (i.e., the “whole” nutrient cycle, including human and natural systems) would have much more significant long-range impact than looking at the store by itself.

Before building a store that is green we need to ask ourselves what impact the activities of the store and co-op have outside the store in relation to meeting the Ends Policies. How might the design of the store influence and be influenced by a deep understanding and willingness to engage in the direction the Ends Policies point us?

This systemic change requires more than a band-aid of simple green building concepts. It requires that we become engaged in how our entire nutrient or energy delivery systems work.

The messy part, again, was that some thought we were talking about a building and others saw that we were learning about sustainable community. Management proposed, and the board agreed, that the next step would be to design a community engagement process to begin a dialogue in our community on topics relating to sustainability in order to inform our planning process. (The community engagement process is on hold in hopes that it is a project the Neighboring Co-ops can take on together.)

Where do our co-op values lead us?

On the heels of our short course on sustainability came another learning opportunity—this one on what it means to be a cooperative. In the summer of 2003, our Cooperative Grocers Association (CGANE) distributed reading material and discussion questions to the boards of the 23 co-ops in our association. Here’s a sampling of discussion questions:

• What are the benefits of collaborating with other co-ops?

• Could our co-op survive and thrive if we were the only food co-op in the country? For how long?

• What does the principle of “cooperation among cooperatives” mean to our co-op?

• Why are we organized as a cooperative?

• What parts of the “Statement of Cooperative Identity” is our co-op most aligned with? What parts are the most challenging for our co-op?

• How can we use the cooperative difference as a competitive advantage?

• What lessons can retail co-ops learn from the experience of the co-op warehouses?

• How can co-ops meet the current and increasing competitive pressure?

• What is important to us about local ownership and local control?

• How are we interdependent (or not) with our fellow co-ops?

• What resources should co-ops invest in research and development for regional and national cooperative strategies?

Our board devoted two hours to these topics at meetings in July, August, and September 2003, and then directors volunteered to write answers to their favorite questions. Our discussions were rich and, with the previous ones on sustainable community, we found we had loosened up all of our “look outward” muscles.

What did we find when we looked? Neighbors! (See illustration: Mind Shift #2.) Of course we knew there were other co-ops around us. The managers had been working together through the Cooperative Grocers Association for a decade, and Northeast Cooperatives had been located in our town. But now—with this much bigger notion of the purpose of our co-op (sustainable community)—we were beginning to see that we would only truly succeed if we combined our efforts with those of others with similar values and goals.

Here’s a nugget from the materials that spoke directly to working with other co-ops on what we had defined as our reason for being:

“The co-op must take the cooperative movement forward, just as the co-op movement must move the co-op toward sustainable community.”

From “Interpretation of self-responsibility, one of the ten co-op values,” by Sidney Pobihushchy.

Neighboring Co-ops: working together with shared purpose

Taking one step forward, we invited board leaders and managers from five neighboring co-ops to join us at our February 2004 board retreat. Here’s an excerpt from the letter we sent them:

For the past year, our board has been discussing the high value of co-op collaboration. Our discussions have ranged from the practical to the visionary, from lowering cost of goods to developing a cooperative economy, from implementing green design to creating a regenerative marketplace. As we enter the planning phase to update our long-range plan, we now see that your participation in the process is key in order to realize the full potential of our future as a co-op.

In the discussions we’ve had about planning the future of our co-op, we’ve taken the position that we must “dissolve the blinders of habitual thought process in order to create the sustainable entity we seek.” So, in contrast to the past, when we have conducted and completed a long-range planning process and then shared the result with you and other neighboring co-ops, we now ask for your participation from the beginning, because we believe that we must build our future together with the co-ops that are nearest to us.

Guess what? They all came! About 30 people from seven co-ops participated in a mind-stretching day talking about what it would mean to work together for our mutual benefit. (This is fundamentally different from earlier work our co-ops have done together, which has been for the benefit of our individual co-ops.) We created a map of our market areas—nearly covering the Connecticut River Valley from Hanover to Northampton—and began to see a regional picture of co-ops with common purpose, with many tens of thousands of members, with significant economic engines, and with deep and broad human resources, working together to create a shared long-range vision supporting sustainable communities. (See illustration: Mind Shift #3.)

The name, Neighboring Co-ops, comes from Wendell Berry: “A viable neighborhood is a community; and a viable community is made up of neighbors who cherish and protect what we have in common.”

The board leaders of neighboring co-ops met several times during the past year to continue the discussion, as did the managers. Directors visited board meetings and annual meetings of other co-ops. Two guiding policies were adopted or discussed by participating co-ops:

“Governance Policy:

The board [of each co-op] shall work with our neighboring co-ops to increase board effectiveness and explore our shared ends.

“Executive Limitations/Means Policy:Management shall not fail to work to create an interdependent cooperative economy with our neighboring co-ops for our mutual benefit.”

(We recognize the imperfection of this language as an Executive Limitations policy, but since not all neighbors use the same governing system we were looking for middle ground.)

A year later, the February 2005 gathering has become the Neighboring Co-op Congress, an event for the full boards of eight participating co-ops and representatives of seven co-ops new to this work. The idea is to have an annual event that brings everyone together, that provides a learning opportunity to help us see the scope of our work, and that provides structure for moving ahead. For newcomers, the event will be an introduction to the concept of our co-ops working together for our mutual benefit and serve as an invitation to participate. We have discovered that participation is work; that the nature of our collaboration challenges how we have been doing things (in isolation) and requires openness to the long-term value of working together as neighbors.

There are many ways to practice reverse isolationism (smile). For example, I recently attended a gathering of representatives of about 20 local groups interested in starting a local chapter of Earth Institute. We introduced ourselves and the purpose of our groups. Before I described the purpose of the Brattleboro Food Co-op, I asked co-op members to raise their hands—that was everyone! Expanding that to the neighborhood level, we are rich with resources. Our work will be to create a beginning vision and embark on a learning and planning path within our communities to direct our efforts and capital. And, in the manner of what has happened so far, one thing will surely lead to another.

For co-op leaders, Andrew Kimbrell’s mindshift from “consumers to creators” is very helpful. With each and every transaction at our stores, we are creating—but what exactly are we creating? Here in the neighborhood, we hope to answer this question together, no longer in isolation.

Brattleboro Food Co-op’s Ends Policies

The purpose of the Brattleboro Food Co-op is to be a sustainable community for a growing number of stakeholders.

The Co-op, as a sustainable community:

• Meets the needs of Co-op shareholders.

• Provides access to healthy food and related products.

• Promotes cooperation, cooperative ownership, and adherence to the Cooperative Principles.

• Embraces environmental responsibility.

• Encourages diversity and addresses viewpoints in a fair and nondiscriminatory manner.

• Maintains an atmosphere that encourages interactions.

(April 2002)

*** Mark Goehring is a consulting with CDS Consulting Co-op (markgoehring@cdsconsulting.coop).